-

|

12 December 2019

|Posteado en : Reportage

9 December is International Anti-Corruption Day and ARAP Ghana, a project managed by FIIAPP, is accompanying Ghanaian institutions in their fight against this crime

INTERNATIONAL ANTI-CORRUPTION DAY

The United Nations has established 9 December as International Anti-Corruption Day. The purpose of this international day is for the media and the organisations involved to contribute to raising awareness of this problem among the public at large.

By corruption we mean “the abuse of power, of functions or means to obtain an economic or other benefit.” If we refer to the etymological origin of the Latin “corruptio”, we find that the original meaning of the term is “action and effect of breaking into pieces.” Corruption is a scourge which, as stated in the United Nations Convention against Corruption, approved on 31 October 2003, threatens the stability and security of societies and undermines justice. As its Latin root indicates, it “breaks apart” both the institutions and the ethical and democratic values of the societies that suffer from it.

In addition, it is a transnational phenomenon in which organised crime usually takes part, resulting in other types of crime such as trafficking in human beings and money laundering.

To combat it, it is essential to promote international cooperation and technical assistance and, for this international cooperation agents such as FIIAPP play a key role.

CORRUPTION IN GHANA

Corruption continues to be a problem that has permeated all sectors of Ghana’s society and economy. With its devastating effects, it impedes sustainable development and is a threat to human rights. It could be said that corruption has been identified as one of the main causes of poverty, deprivation and underdevelopment. In the particular case of Ghana, the prevalence of corruption has resulted in poor provision of services and a lack of access to other basic services such as health and education. Corruption is also a threat to Ghana’s democratic ideals, in particular the rule of law, justice and equality before the law.

According to the 2018 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, Ghana ranks 78th out of 180 countries.

THE ARAP-GHANA PROJECT

The Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Programme (ARAP), funded by the European Union and implemented by FIIAPP, has been supporting the efforts of the Ghanaian government to reduce corruption for three years.

The aim of the project is to promote good governance and support national reform, in order to improve accountability and strengthen anti-corruption initiatives throughout the country. To this end, it works together with the relevant government institutions and other national strategic partners while at the same time improving accountability and respect for existing legal structures.

In addition, it acts as a support programme for the government in implementing the National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP), Ghana’s national anti-corruption strategy ratified by Parliament in 2014, which aims to create a democratic and sustainable Ghanaian society based on good governance and endowed with a high degree of ethics and integrity.

ANTI-CORRUPTION AND TRANSPARENCY WEEK

In light of this problem, from 2 to 9 December Accra, the country’s capital, held the Anti-Corruption and Transparency Week (ACT) in which the Government, the public and private sectors, academia, the media, civil society and the general public all took part. The week was organised by the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) supported by the ARAP programme.

The purpose of ACT Week was to create a platform for assessing the impact of the NACAP in the first five years of its implementation and strengthening the commitment of the implementing partners in the remaining five years of the NACAP; to raise awareness among Ghanaians of the perverse effects of corrupt practices; to advocate for sustained collaboration and inter-institutional partnership in the fight against corruption as well as for the need to provide adequate resources to anti-corruption agencies; and to promote the use of international cooperation instruments in the fight against corruption.

The week included a large number of activities, both nationally and regionally. These included the international forum on money laundering and asset recovery, international cooperation in legal and other areas; the forum on integrity for youth; the NACAP high-level conference; the presentation of integrity awards; and the observance of international anti-corruption and human rights days.

The work of ARAP will continue not only during the week but every day until the end of the programme in December 2020, because the fight is not just for one week, but for every day of the year.

Text created with the collaboration of Sandra Quiroz, communication specialist of ARAP Ghana

-

|

07 February 2019

|Posteado en : Interview

Shamima Muslim, ARAP project specialist, reflects in this interview on the role of the media when they raise issues of corruption, particularly in the case of Ghana

As a media worker and specialist on the ARAP project (Ghana’s Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Programme), funded by the European Union and managed by FIIAPP, do you think that the media address the issue of corruption?

We have been reflecting on this since I started in the media in 2008. Even before that, corruption has always been a key issue, especially at election time. All politicians and political parties who campaign and come to power always have it in the spotlight, they fight against corruption in their public speeches and insist on the need to be accountable. So we recognise that it exists.

And do you think that the media is sensitive to corruption?

We have not given our best. Well, maybe we have given our best, but the best has not been enough. Since the media is a news industry, when a big new corruption issue appears, everything is immediately told, but then people go on with their lives and their problems and they have already forgotten by the following news story. I think we have to develop a culture that is slightly different from the culture of the cursor and Google, which is what we have been doing.

So, do you think that the media should play a more active and permanent role in corruption issues?

The media have to do more than they are doing right now because both the media and the people who work in them should be the eyes of society.

The mass media is a powerful tool for socialisation. If we use them efficiently, we will make citizens aware of many things: cases of fraud, theft, contract inflation, etc., all of the issues that reduce public resources and prevent State players from making the proper investments in social services.

But we need support, for example, by targeting certain key influencers in the media and making them part of this process of holding leaders accountable. Newscasters who present the morning magazine programme, professionals who do night programmes, professionals who give the news, etc. You need them to be part of the process. And so we get an ally who has the power of the microphone and who is able to ask the important questions, thanks to the point of view they have acquired.

What role can social media play in this awareness?

Information, information, information. Social networks are the future, but we must also remember that not everyone is on them. Internet access is still very expensive in most of Africa and virtually non-existent in some communities. So maybe you are not able to use social networks for an appropriate general mobilisation of society, of citizens, from different economic strata. Especially if you want general collective action.

But even so, social networks are very useful: we have seen what has happened in Ghana. We have seen campaigns on social networks that have forced the Government to change certain policies. When the government wants to introduce a new policy and we say it’s a bad idea … There was a case where the government said, “If you do not pay for your television licence, you will have to go to court.“ All this brought a great public uproar: it was a campaign organised purely on social networks. Influencers and young people on social media protested and protested. In a few hours, or a day or two, it was announced that this policy was not going to be implemented.

So social networks are a powerful tool to mobilise a certain group of people who share the same ideas, who are a little more informed. There are some people who are influencers on social networks and who, when they open discussions on their walls, generate arguments.

What do citizens achieve with all this?

If the media play their role, we, the citizens, will be able to force our leaders to be accountable, because they know that the media will always be watching them until things are done well.

-

|

11 October 2018

|Posteado en : Opinion

The Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Programme, managed by the FIIAPP in Ghana, supports the fight against corruption in the African country

Earlier this year, the World Bank published its forecast for global economic growth for 2018, a forecast that featured Africa prominently. With an estimated growth of 8.3%,Ghana led a ranking in which sub-Saharan countries held the top positions. In addition to Ghana, Ethiopia (2nd), Ivory Coast (4th) and Djibouti (5th) were among the five countries with the highest growth forecasts. This aspect of the Ghanaian economy does not come as a surprise. With 34 years of uninterrupted growth (the last recession dates from 1983, when its economy shrunk by 4.5%), Ghana has one of the most diverse and dynamic economies in sub-Saharan Africa—the eighth largest in terms of GDP and the second largest in West Africa after Nigeria—and has a fairly balanced trade balance, which places it as a low-middle income country.

Inequality versus macroeconomics

However, these macroeconomic data cannot hide other indicators that are not so encouraging. Although the population living in extreme poverty has halved in the last 25 years, from 52% in 1992 to 24% today, Ghana is one of the 50 most unequal countries in the world and, as Oxfam points out in its latest reports, “inequality [in Ghana] is increasing, undermining the reduction of poverty, slowing economic growth and threatening social stability.” According to data from this NGO, in Ghana the 10% of the richest population consumes almost a third of the resources (32%), the same amount consumed by the poorest 60%. At the other end of the scale, the poorest 10% only has access to 2% of the resources.

This problem is compounded by two important gaps. In the first place, the gender gap, which causes women to have very restricted access to resources and wealth. As Oxfam points out, this group is “half as likely as men to own land”. In addition, “only 6% of the richest people in Ghana are women”. Second, there is a territorial gap. Ghana’s development pattern has accentuated the north/south and country/city divisions, with poverty fundamentally located in rural areas (almost four times more than in urban areas); and in the three northern provinces (the Upper East, Upper West and Northern regions), which have development indicators similar to countries such as Mauritania, Madagascar or Benin, according to the 2015 Human Development Report.

Regiones de Ghana de menor a mayor IDH y país equivalente Región IDH País equivalente Northern 0,483 Benín Upper West 0,506 Madagascar Upper East 0,508 Mauritania Central 0,535 Angola Brong Ahafo 0,571 Santo Tome y Príncipe Eastern 0,575 Santo Tome y Príncipe Ghana (nacional) 0,578 – Volta 0,581 Zambia Ashanti 0,588 Laos Western 0,609 Bután Greater Accra 0,647 Marruecos Fuente: Subnational Human Development Index de Global Data Lab Anti-corruption in the face of inequality

To enable government action in countries affected by inequality to reverse the situation, emphasis should be placed on three aspects, as indicated in the Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index: social spending, tax policies and workers’ rights, and corruption is a phenomenon that negatively impacts these three aspects. Firstly, by detracting from public resources, corruption significantly affects social policies, which have less spending capacity. Secondly, since it is an opaque economic circuit, it is not taxed. In addition, on many occasions, large-scale corruption and tax evasion are interconnected phenomena that involve political and economic elites. Without forgetting that the social perception of corruption is a great disincentive for compliance with tax obligations by citizens, who think that their taxes will end up in the pockets of the rulers. Lastly, corruption encourages informal employment, where it is more difficult to adopt regulations that promote respect for workers’ rights and the establishment of decent minimum wages.

In short, as Transparency International pointed out in the presentation of the Corruption Perception Index 2016, “systemic corruption and social inequality reinforce each other, creating a vicious circle between corruption, unequal distribution of power in society and unequal distribution of wealth”. This is exactly what happens in Ghana. The perception of corruption in the country, measured by the aforementioned index, yields a medium-high score of 40 out of 100. This index indicates the degree of corruption in the public sector according to the perception of the business sector and country analysts, on a scale from 100 (perception of absence of corruption) and 0 (perception as very corrupt). But there is a more alarming fact, namely that Ghana´s result has been deteriorating in recent years, from 48/100 in 2014 to 40/100 in 2017. Quite probably, this worsening is largely due to the revelation in recent years of important corruption cases that affected the judicial system and the football federation.

Tax evasion, which, as we pointed out, is a matter closely linked to corruption, is also an important challenge for Ghana. In fact, for Ghana’s Business Development Minister, it is the biggest challenge the country faces. All of this means that the fight against corruption in Ghana is a powerful tool for inclusive development, which goes beyond mere macroeconomic growth and considers the most disadvantaged groups. And that is the goal of Ghana’s Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Programme (ARAP), which is managed by the FIIAPP in Ghana with funding from the European Commission: to reduce corruption and improve accountability in this African country. This project begins at a time when the government of Ghana has been intensely involved in the fight against corruption, creating Ghana´s National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP) within which the project is framed.

Ángel González, technical coordinator of the transparency and anti-corruption support project in Ghana

-

|

13 April 2018

|Posteado en : Reportage

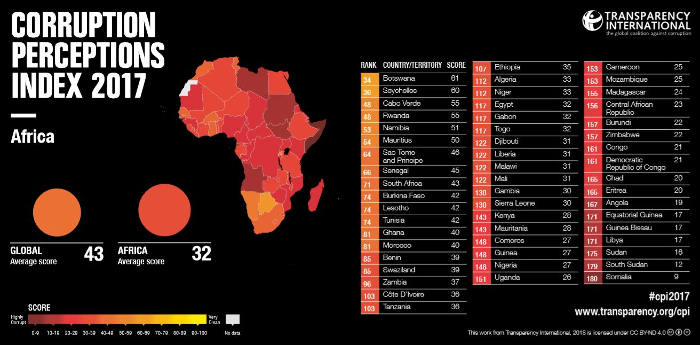

The Ghana-ARAP Project relies on institutions to get the public involved. According to Transparency International, sub-Saharan Africa is the worst–rated region in this respect

“Having to pay for a service we have a right to receive – do you think that is corruption?” Barbara Mensah asks the people of Ghana, referring to one of the most burning questions of our time. She is one of the Civic Education Officers responsable for investigating perceptions of corruption in Ghana.

“I am going to ask about certain practices, you tell me if you think they are corrupt” was the question put by another of these officers, Jafaru Omar. Through a questionnaire, officers appointed by Ghana’s National Commission for Civic Eduction (NCCE) survey the views of citizens in different parts of the country.

On the ground, the findings are already clear: of the 8672 responses, over half those surveyed (58.4%) have been witnesses to some form of corruption. Henrrieta Assante-Sharpong, in charge of the investigation, says: “the findings show that although Ghanaians are aware of corruption, they have very little knowledge of the various ways it may be practised.”

The NCCE was set up for the purpose of increasing public awareness: “Our lives are going backwards. We don’t have roads, there is no electricity. The money gained from corruption could have been used for these services”, says Aluliga Malpang, a farmer from the Tengzuk Community. Sub-Saharan Africa is the worst-rated region for corruption, according to the most recent report from Transparency International.

Cooperation in a hostile climate

The report on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) rates 180 countries and territories according to perceived levels of corruption in the public sector, using a scale of zero to 100, where zero is extremely corrupt and 100 highly transparent.

New Zealand and Denmark are highest-placed in 2017, with scores of 89 and 88 respectively. Syria, South Sudan and Somalia have the lowest scores, with 14, 12 and 9 respectively. Ghana is in 81st place, with 40 points – a score above the average for the sub-Saharan region (32 points).

Nevertheless, the study shows that over two-thirds of countries had scores below 50. Transparency International works internationally and locally in over 100 countries in the world: “giving a voice to the victims of corruption, working with governments, undertakings and citizens to stop the abuse of power or bribery”. It states that most countries are making little or no progress in putting an end to corruption.

Ghana does not want to be in that category. Its initiative is part of the Anti-Corruption, Rule of Law and Accountability” programme. It is a project in support of transparency, with the aim of reducing corruption and improving accountability in the African country. For four and a half years, FIIAPP has been managing this programme, financed by the European Union, in collaboration with GIZ (Germany) and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

“I want to help solve the corruption problem”, said Joseph Samuel Bebefiankom, a student in Kwashieman (Accra). Like him, other citizens say “it could be reduced, cut back”, “that will provide jobs for a lot of people” “it will help the country to develop.” They know what they want to achieve, but not how to achieve it.

A number of Ghanaian public institutions such as the NCCE, in collaboration with FIIAPP, have designed a strategy to involve the public, as well as others, in the struggle against corruption. One of the priorities of Ghana-ARAP is to raise their awareness of the importance of reporting it.

The more leaders that get involved, the less corruption there will be

The África no es un país [‘Africa is not one country’] blog reminds us, in the same report, that “2017 has seen the fall of a number of rulers accused of encouraging corruption”: Yahya Jammeh in Gambia, José Eduardo dos Santos in Angola, Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and, already in 2018, Jacob Zuma of South Africa.

George Obeng Obei is another Civic Education Officer. He says “people without much education don’t know how things are done in assemblies and in institutions. But they do believe there are elements of corruption in them”, Not knowing how it works doesn’t mean they don’t see it. They know, they are aware, according to Obeng Obei, that you can only get things with money. And this mindset has to be changed.

ARAP Ghana workshop According to Transparency International, it is the right time to “redefine” the problem in Africa, as, in some cases, the CPI points to a “hopeful future” for the continent. In spite of being the worst region overall, some countries have made significant progress, such as Botswana (61), which has a higher rating than Spain (59).

The key, according to the organisation, is that these countries have “a political leader committed to fighting corruption.” That is why they go further in developing laws and institutions in this regard. Ghana is making efforts in this direction, and its government has introduced a National Anti-corruption Action Plan (NACAP) to steer the project.

If the public at large also gets involved, success will be one step closer. The president of the NCCE, Josephine Nkrumah, knows this. She assesses the investigation conducted in the country: “NCCE will use this report to create civic education actions. To win the battle, we have to get both the public and the private sector involved. And what is even more important is getting every Ghanaian man and woman involved.”

“Winning the fight against corruption” is the African Union (AU)’s motto for 2018. This phrase could be said to apply to almost the whole world. It stems from the premise that “corruption rewards those who disobey the rules, destroying all the endeavours of constructive, just and equitable governance”.

The areas investigated in Ghana are shown in this video:

-

|

28 September 2017

|Posteado en : Reportage

To date Ghana does not have a Freedom of Information law but it has made some positive strides to ensure transparency and accountability

In the past years, Ghana has made some positive strides to ensure transparency and accountability within its governance reforms. Some concrete commitments include the development and roll out of a 10 year National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP) as well joining in 2011 the Open Government Partnership.

As part of these efforts, there is also the five-year EU funded Accountability, Rule of law and Anti-corruption Programme (ARAP) currently implemented by FIIAPP. The objective of the programme is to contribute to current reform processes to reduce corruption and improve accountability, and compliance with the rule of law, particularly when it comes to accountability, anti-corruption and environmental governance. It does so through support key institutions, while at the same time increasing the ability of the public, civil society organizations and the media to hold government to account.

On one hand the programme works with state institutions to improve and strengthen the services to report, prosecute and adjudicate corruption cases. On the other, it strengthens state institutions, civil society and the media to create the conditions for citizens to demand accountability from the government and report corruption cases.

Against this backdrop, access to information is a critical stepping stone for anyone who wishes to hold the government to account. It is no surprise therefore that access to information has become a cornerstone of good governance and an important anti-corruption tool. Information is fundamental to make informed decisions. Information is also power. Where it is not freely accessible, corruption can thrive and basic rights might not be realised. People can hide corrupt acts behind a veil of secrecy. Those with privileged access to information can demand bribes from others also seeking it.

ARAP contributes to current reform processes to reduce corruption and improve accountability in Ghana Today, 28th of September, is the International Day for Universal Access to Information. Citizens and organizations across the world call on their leaders today to act upon the fundamental premise that all information held by governments and governmental institutions is in principle public and may only be withheld if there are legitimate reasons, such as typically privacy and security, for not disclosing it.

The International Day for Universal Access to Information was declared just over two years ago by UNESCO. Not many know however that this UN initiative has its roots in Africa, and is an outcome of advocacy of the African Platform on Access to Information (APAI). This is a concerted effort to remind us all – regardless of our job and daily life – that accessing information held by government officials and institutions is a fundamental human right established under international Law, covered by Article 19 of the International Declaration of Human Rights and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Over the past 10 years, the right to information has been recognized by an increasing number of countries, through the adoption of a wave of Freedom of Information (FOI) laws. In 1990, only 13 countries had adopted national FOI laws, whereas there are currently more than 90 such laws adopted across the world.

To date Ghana does not have a Freedom of Information law, despite it has been debated in the country for almost 20 years: the actual bill being drafted in 1999 and then reviewed in 2003, 2005 and 2007 and is currently in Parliament. There are however, positive signs from the government affirming that the bill will be approved in the coming year together with the Office of the Special Prosecutor for Corruption.

Riccardo D’Emidio, Civic Education Expert – Accountability, Rule of law and Anti-corruption Programme (ARAP)