-

|

29 July 2021

|Posteado en : Interview

We interviewed the Magistrate-Judge, Óscar Rey, of the Civil Registry of Seville who participates in the cooperation project, managed by FIIAPP and AECID, to support the fight against corruption in Mozambique. It is part of the FIIAPP’s #PublicTalent, mobilised in more than 100 countries.

What has been the greatest achievement of your experience as a mobilised expert?

The greatest achievement so far has been to have been able to get Mozambican institutions to trust in the ability of the Support for the Fight Against Corruption in Mozambique project to work with them to effectively fight against corruption and get their full participation.

What are you most proud of?

From the teamwork and effort deployed, up to now, with my colleagues at FIIAPP when it comes to defending public technical assistance as an outstanding value.

How has your mission as an aid worker and at the same time a public official contributed to improving the lives of people and the planet?

As a Magistrate, I view public service to citizens as an absolute priority and as a necessary asset for the well-being of society as a whole. I understand that it is important to export these values and knowledge to other countries through the public technical assistance promoted by FIIAPP.

What is the main value of the public aspect for you?

Technical capacity and experience, merit and capacity in the selection of professionals, and prioritisation in the professional exercise of the principles of impartiality, objectivity and independence.

What learning would you highlight?

That, sometimes, it is not easy to defend what is public against the commercialism of the market, private consultancies and vested interests. But there is no doubt that in the public sphere there are magnificent professionals who are knowledgeable about daily practice, and that this public model must be defended despite the obstacles.

-

|

25 July 2019

|Posteado en : Reportage

Money laundering is closely related to crimes such as drug trafficking, corruption and organized crime. At FIIAPP we work to fight this problem through a wide range of projects

The concept of “money laundering” arose during the 1920s in the United States. American mafias, dedicated to the smuggling of alcoholic beverages, created a network of laundries to hide the illicit origin of the money derived from this business.

As explained by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), money laundering is “the method used by infractors to hide the illegal origins of their wealth and protect their income, with the goal of flying under the radar of institutions in charge of investigation and law enforcement”.

The United Nations has the Financial Action Task Force, which sets standards to organize the legislative architecture of the fight against money laundering by organized crime .

UNODC also emphasizes that individuals and terrorist organizations employ techniques similar to those practised by people who are involved in money laundering to hide their resources. All these techniques carry with them crimes such as corruption or organized crime.

In this regard, the Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund , Min Zhu, notes that “money laundering and terrorist financing are financial crimes that have economic consequences . They can threaten the stability of a country’s financial sector or its external stability in general. Effective regimes to combat money laundering and terrorist financing are essential to safeguarding the integrity of markets and the global financial framework, as they help mitigate the factors that lead to financial abuse.”

Along these lines, we must emphasize that money generated by criminal activities is difficult to hide. Over the years, States have reinforced the mechanisms necessary to identify, seize and confiscate that money wherever it is. “Measures to prevent and combat money laundering and terrorist financing, therefore, are not just a moral imperative, but an economic need,” according to Zhu.

2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goal 16

Spain, together with the 193 countries of the United Nations, pledged to comply with the 2030 Agenda, approved by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015. In this context, the non-governmental organization Transparency International (IT) has published a report, which takes April to June 2018 as its reference, in order to examine the progress of Spain in relation to Sustainable Development Goal 16, based on promoting a just, peaceful and inclusive society, which contains goals related to transparency and fighting against corruption . This document focuses on the situation of illicit financial flows, bribery and corruption in all its forms, transparent and accountable institutions, public freedoms, and the right to access information.

In addition, the report highlights that, although Spain has made great strides at the legislative level on this matter, “it is necessary that the institutions constituting the first line of prevention and fighting against corruption, such as the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor, remain totally independent from political power.” Likewise, “Spain has the challenge of achieving a homogeneous and effective legal framework in all matters related to public integrity and accountability, and at all territorial levels.”

FIIAPP works on the fight against money laundering

FIIAPP is working on the fight against money laundering through a variety of projects.

EL PAcCTO is a European Union programme implemented by FIIAPP and Expertise France with the support of IILa and Camões. The main goal of this project is the fight against transnational organized crime and the strengthening of the institutions responsible for guaranteeing citizen security in 18 countries in Latin America.

“EL PAcCTO aims to address various challenges and, thanks to the exchanges in working groups and the presentation of practical cases, also identify the difficulties and weaknesses specific to Latin America and identify possible coordination difficulties between the agents in the fight against money laundering”, highlights Jean Dos Santos, an EL PacCTO project expert.

Additionally, a project called European Support for Bolivian Institutions in the Fight against Drug Trafficking and Related Crimes places special emphasis on money laundering. The project has sought to improve capability through training courses. It has focused on strengthening inter-institutional coordination and international cooperation and has given aid support to overcome the fourth round of the Mutual Evaluation of the Financial Action Task Force Group of Latin America.

“Whether or not the Bolivian State can remain off the famous black or grey lists comprised of States that have neither established prevention measures against money laundering nor committed themselves to doing so depends in large part on passing this Mutual Evaluation”, emphasized Javier Navarro, National Police Inspector and expert on this project.

Following this same line of work, the EU Law Enforcement Support Project in the fight against drugs and organized crime in Peru seeks to improve the effectiveness of training schools, inter-institutional cooperation and Peruvian intelligence systems in order to fight drugs, organized crime and money laundering.

Likewise, EU-ACT projects on Action against Drugs and Organized Crime and SEACOP are also active in the fight against money laundering, a problem closely related to drug trafficking and organized crime.

“Drug trafficking organizations are present in different countries. The materials may be supplied by one country, others may be transit countries, others destination countries, etc. Money laundering may take place in yet other countries. Therefore, if this is not addressed from a transnational standpoint, it is impossible to deal with,” explains José Antonio Maté, EU-ACT Project Coordinator for the Central Asia area.

With the ARAP-Ghana project , ‘Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption of Ghana’, the goal is to reduce corruption and improve accountability in the African country, taking into account the money laundering that corruption brings. Ghana has created the National Anti-Corruption Plan (NACAP), of which this project is part.

Finally, in the El PacCTO:Supporting AMERIPOL project it is expected that money laundering will be incorporated into the technological platform for the exchange of police information that this project is promoting in Latin America.

-

|

04 July 2019

|Posteado en : Opinion

The Open Justice Strategy of the State Council of Colombia, supported by the ACTUE Colombia project, has received a stellar reform award.

Early last month, I was fortunate enough to attend the 6th Global Summit of the Open Government Partnership in Canada , a gathering that brought together two thousand people from 79 countries and 20 local governments who, along with civil society organizations, academics and other stakeholders, make up the Open Government Partnership (OGP). This year, the Summit revolved around three strategic priorities: participation, inclusion and impact.

During the inauguration, and to my surprise, the initiative that we supported in the ACTUE project – a project managed by FIIAPP with EU funding between 2014 and 2018 – was displayed on giant screens: the Open Justice Strategy in the State Council of Colombia as one of the “ Stellar Reforms” selected in the last OGP cycle. It was very exciting to be able to experience that tangible impact of one of our projects, something that we rarely get to experience. I was even more thrilled than when I saw the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau live, which is really saying something. And for good reason, too. These 12 commitments have been selected by the Independent Review Mechanism from among hundreds of others for showing evidence of preliminary results that mean significant advances in relevant and transformative political areas .

The Open Justice Strategy in the Council of State of Colombia has, for the first time, allowed the Court to begin publishing its previous agendas and decisions, as well as information on possible conflicts of interest of judges and administrative staff; essential aspects of public accountability, as well as enabling citizens and civil society to do their work of social control. In the long term, these changes can reduce corruption in justice institutions and allow them to regain the trust of citizens . Justicia Abierta is one of the political tendencies in open government that is gaining greater traction, given the major impact that its actions can have on citizens; In particular, access to justice makes it possible to exercise other rights. In addition, this sectoral action contributes directly to the advancement of the 2030 Agenda through goal 16, Peace, Security and Solid Institutions.

The ACTUE Colombia project was supporting the Transparency Secretariat of Colombia in the preparation of its OGP action plans, as well as civil society organizations, by using specialized technical assistance to promote the creation of a space for dialogue between administrations and civil society to define their own priorities in open government .

This is a good example of the positive impact that delegated cooperation can have, thanks to the flexibility and innovation they bring to our partners and the technical assistance on demand that we carry out.

About the ACTUE-Colombia project

The Anti corruption and Transparency Project of the European Union for Colombia (ACTUE-Colombia) has supported Colombian institutions in the implementation of key measures for a Open Territorial Government with the aim of making progress in the prevention of and fight against corruption both at the national and territorial levels. To this end, the project supported the creation of conditions for the fulfilment of international commitments, the strengthening of social control, the promotion of the co- responsibility of the private sector, and the generation of cultural and institutional changes .

The project is financed by the European Union and managed by FIIAPP in coordination with the Secretary for Transparency (ST) and Public Function (FP). It has assisted three regional governments, six city councils and two hospitals in areas such as applying the Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information, drafting Anti-Corruption and Citizen Information Plans (PAAC), fostering accountability and promoting public participation. It has thus helped officials to understand that the right to transparency and access to information is an essential right on which other rights depend. It has increased their awareness by institutionalizing advances in active transparency and their knowledge of how to identify and manage the risks of corruption.

Carolina Díaz, legal technician in the area of Justice and Security at FIIAPP and, between 2014 and 2018, member of the ACTUE Colombia team

-

|

11 October 2018

|Posteado en : Opinion

The Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Programme, managed by the FIIAPP in Ghana, supports the fight against corruption in the African country

Earlier this year, the World Bank published its forecast for global economic growth for 2018, a forecast that featured Africa prominently. With an estimated growth of 8.3%,Ghana led a ranking in which sub-Saharan countries held the top positions. In addition to Ghana, Ethiopia (2nd), Ivory Coast (4th) and Djibouti (5th) were among the five countries with the highest growth forecasts. This aspect of the Ghanaian economy does not come as a surprise. With 34 years of uninterrupted growth (the last recession dates from 1983, when its economy shrunk by 4.5%), Ghana has one of the most diverse and dynamic economies in sub-Saharan Africa—the eighth largest in terms of GDP and the second largest in West Africa after Nigeria—and has a fairly balanced trade balance, which places it as a low-middle income country.

Inequality versus macroeconomics

However, these macroeconomic data cannot hide other indicators that are not so encouraging. Although the population living in extreme poverty has halved in the last 25 years, from 52% in 1992 to 24% today, Ghana is one of the 50 most unequal countries in the world and, as Oxfam points out in its latest reports, “inequality [in Ghana] is increasing, undermining the reduction of poverty, slowing economic growth and threatening social stability.” According to data from this NGO, in Ghana the 10% of the richest population consumes almost a third of the resources (32%), the same amount consumed by the poorest 60%. At the other end of the scale, the poorest 10% only has access to 2% of the resources.

This problem is compounded by two important gaps. In the first place, the gender gap, which causes women to have very restricted access to resources and wealth. As Oxfam points out, this group is “half as likely as men to own land”. In addition, “only 6% of the richest people in Ghana are women”. Second, there is a territorial gap. Ghana’s development pattern has accentuated the north/south and country/city divisions, with poverty fundamentally located in rural areas (almost four times more than in urban areas); and in the three northern provinces (the Upper East, Upper West and Northern regions), which have development indicators similar to countries such as Mauritania, Madagascar or Benin, according to the 2015 Human Development Report.

Regiones de Ghana de menor a mayor IDH y país equivalente Región IDH País equivalente Northern 0,483 Benín Upper West 0,506 Madagascar Upper East 0,508 Mauritania Central 0,535 Angola Brong Ahafo 0,571 Santo Tome y Príncipe Eastern 0,575 Santo Tome y Príncipe Ghana (nacional) 0,578 – Volta 0,581 Zambia Ashanti 0,588 Laos Western 0,609 Bután Greater Accra 0,647 Marruecos Fuente: Subnational Human Development Index de Global Data Lab Anti-corruption in the face of inequality

To enable government action in countries affected by inequality to reverse the situation, emphasis should be placed on three aspects, as indicated in the Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index: social spending, tax policies and workers’ rights, and corruption is a phenomenon that negatively impacts these three aspects. Firstly, by detracting from public resources, corruption significantly affects social policies, which have less spending capacity. Secondly, since it is an opaque economic circuit, it is not taxed. In addition, on many occasions, large-scale corruption and tax evasion are interconnected phenomena that involve political and economic elites. Without forgetting that the social perception of corruption is a great disincentive for compliance with tax obligations by citizens, who think that their taxes will end up in the pockets of the rulers. Lastly, corruption encourages informal employment, where it is more difficult to adopt regulations that promote respect for workers’ rights and the establishment of decent minimum wages.

In short, as Transparency International pointed out in the presentation of the Corruption Perception Index 2016, “systemic corruption and social inequality reinforce each other, creating a vicious circle between corruption, unequal distribution of power in society and unequal distribution of wealth”. This is exactly what happens in Ghana. The perception of corruption in the country, measured by the aforementioned index, yields a medium-high score of 40 out of 100. This index indicates the degree of corruption in the public sector according to the perception of the business sector and country analysts, on a scale from 100 (perception of absence of corruption) and 0 (perception as very corrupt). But there is a more alarming fact, namely that Ghana´s result has been deteriorating in recent years, from 48/100 in 2014 to 40/100 in 2017. Quite probably, this worsening is largely due to the revelation in recent years of important corruption cases that affected the judicial system and the football federation.

Tax evasion, which, as we pointed out, is a matter closely linked to corruption, is also an important challenge for Ghana. In fact, for Ghana’s Business Development Minister, it is the biggest challenge the country faces. All of this means that the fight against corruption in Ghana is a powerful tool for inclusive development, which goes beyond mere macroeconomic growth and considers the most disadvantaged groups. And that is the goal of Ghana’s Accountability, Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Programme (ARAP), which is managed by the FIIAPP in Ghana with funding from the European Commission: to reduce corruption and improve accountability in this African country. This project begins at a time when the government of Ghana has been intensely involved in the fight against corruption, creating Ghana´s National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP) within which the project is framed.

Ángel González, technical coordinator of the transparency and anti-corruption support project in Ghana

-

|

13 April 2018

|Posteado en : Reportage

The Ghana-ARAP Project relies on institutions to get the public involved. According to Transparency International, sub-Saharan Africa is the worst–rated region in this respect

“Having to pay for a service we have a right to receive – do you think that is corruption?” Barbara Mensah asks the people of Ghana, referring to one of the most burning questions of our time. She is one of the Civic Education Officers responsable for investigating perceptions of corruption in Ghana.

“I am going to ask about certain practices, you tell me if you think they are corrupt” was the question put by another of these officers, Jafaru Omar. Through a questionnaire, officers appointed by Ghana’s National Commission for Civic Eduction (NCCE) survey the views of citizens in different parts of the country.

On the ground, the findings are already clear: of the 8672 responses, over half those surveyed (58.4%) have been witnesses to some form of corruption. Henrrieta Assante-Sharpong, in charge of the investigation, says: “the findings show that although Ghanaians are aware of corruption, they have very little knowledge of the various ways it may be practised.”

The NCCE was set up for the purpose of increasing public awareness: “Our lives are going backwards. We don’t have roads, there is no electricity. The money gained from corruption could have been used for these services”, says Aluliga Malpang, a farmer from the Tengzuk Community. Sub-Saharan Africa is the worst-rated region for corruption, according to the most recent report from Transparency International.

Cooperation in a hostile climate

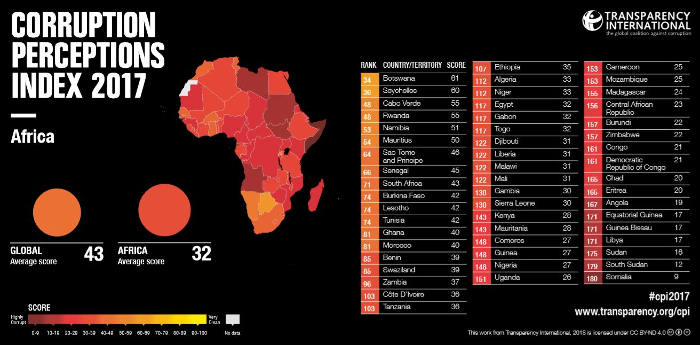

The report on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) rates 180 countries and territories according to perceived levels of corruption in the public sector, using a scale of zero to 100, where zero is extremely corrupt and 100 highly transparent.

New Zealand and Denmark are highest-placed in 2017, with scores of 89 and 88 respectively. Syria, South Sudan and Somalia have the lowest scores, with 14, 12 and 9 respectively. Ghana is in 81st place, with 40 points – a score above the average for the sub-Saharan region (32 points).

Nevertheless, the study shows that over two-thirds of countries had scores below 50. Transparency International works internationally and locally in over 100 countries in the world: “giving a voice to the victims of corruption, working with governments, undertakings and citizens to stop the abuse of power or bribery”. It states that most countries are making little or no progress in putting an end to corruption.

Ghana does not want to be in that category. Its initiative is part of the Anti-Corruption, Rule of Law and Accountability” programme. It is a project in support of transparency, with the aim of reducing corruption and improving accountability in the African country. For four and a half years, FIIAPP has been managing this programme, financed by the European Union, in collaboration with GIZ (Germany) and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

“I want to help solve the corruption problem”, said Joseph Samuel Bebefiankom, a student in Kwashieman (Accra). Like him, other citizens say “it could be reduced, cut back”, “that will provide jobs for a lot of people” “it will help the country to develop.” They know what they want to achieve, but not how to achieve it.

A number of Ghanaian public institutions such as the NCCE, in collaboration with FIIAPP, have designed a strategy to involve the public, as well as others, in the struggle against corruption. One of the priorities of Ghana-ARAP is to raise their awareness of the importance of reporting it.

The more leaders that get involved, the less corruption there will be

The África no es un país [‘Africa is not one country’] blog reminds us, in the same report, that “2017 has seen the fall of a number of rulers accused of encouraging corruption”: Yahya Jammeh in Gambia, José Eduardo dos Santos in Angola, Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and, already in 2018, Jacob Zuma of South Africa.

George Obeng Obei is another Civic Education Officer. He says “people without much education don’t know how things are done in assemblies and in institutions. But they do believe there are elements of corruption in them”, Not knowing how it works doesn’t mean they don’t see it. They know, they are aware, according to Obeng Obei, that you can only get things with money. And this mindset has to be changed.

ARAP Ghana workshop According to Transparency International, it is the right time to “redefine” the problem in Africa, as, in some cases, the CPI points to a “hopeful future” for the continent. In spite of being the worst region overall, some countries have made significant progress, such as Botswana (61), which has a higher rating than Spain (59).

The key, according to the organisation, is that these countries have “a political leader committed to fighting corruption.” That is why they go further in developing laws and institutions in this regard. Ghana is making efforts in this direction, and its government has introduced a National Anti-corruption Action Plan (NACAP) to steer the project.

If the public at large also gets involved, success will be one step closer. The president of the NCCE, Josephine Nkrumah, knows this. She assesses the investigation conducted in the country: “NCCE will use this report to create civic education actions. To win the battle, we have to get both the public and the private sector involved. And what is even more important is getting every Ghanaian man and woman involved.”

“Winning the fight against corruption” is the African Union (AU)’s motto for 2018. This phrase could be said to apply to almost the whole world. It stems from the premise that “corruption rewards those who disobey the rules, destroying all the endeavours of constructive, just and equitable governance”.

The areas investigated in Ghana are shown in this video:

-

|

31 August 2017

|Posteado en : Reportage

The ACTUE-Colombia project seeks to strengthen transparency and integrity in the Colombian public and privates sectors and in civil society

Colombia drags behind it the tragic figure of 218 thousand deaths and nearly six million displaced persons, all attributable to an armed conflict that lasted for over fifty years. A conflict that assails Colombian society at all levels, where one of the major factors responsible for the perpetuation of this context of violence has been corruption.

Today Colombia is looking forward, placing all its hopes on an arduous peace process that must take into account all stakeholders in society. A key piece in advancing in this peace process is the commitment to transparency and prevention of corruption in both the country’s public institutions and private entities.

Along these lines, the ACTUE-Colombia project was launched in 2014 as a response of the European Union to a request from the Colombian government for strengthening and implementation of public policies aimed at fighting corruption. This is a project funded by the European Union and managed by FIIAPP that works hand in hand with various Colombian public institutions, such as the Secretariat of Transparency, the Civil Service Department, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Mines, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Council of State, as the representative of the judiciary, among others.

This project seeks to create a comprehensive approach in corruption prevention that will work from four strategic areas with special impact in the country:

Public Integrity and Open Government: Creation of an open and transparent government through instruments such as the transparency and access to public information law, accountability, citizen participation, public ethics, whistleblower protection, among others. As expressed by Liliana Caballero, director of the Civil Service Administration Department, “for the government it is very important that citizens trust the State and the employees of public administrations, and citizens should have the security that they have access to all the information, that there is no longer any secrecy in any proceedings, in the budgetsâ€.

Version:1.0 StartHTML:000000224 EndHTML:000003796 StartFragment:000003501 EndFragment:000003748 StartSelection:000003501 EndSelection:000003748 SourceURL:https://www.fiiapp.org/wp-admin/post.php?post=7856&action=edit

Sectoral Action: to foster integrity and transparency, it is also necessary to act in specific sectors such as judicial bodies, health, the extractive industries and a culture of integrity.

- Colombia’s Council of State is working to promote transparency, accountability and judicial ethics. To serve as a precedent, the Council of State on 29 June held a public hearing for accountability, which was the first time a judicial body had ever organised an accountability event in the country.

- The extractive industry is one of the most important economic sectors in Colombia; in 2015 the extractive industry was responsible for 7.2% of the country’s GDP, and therefore it is important to keep this economic activity clear of networks of corruption. To accomplish this, implementation of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) throughout the country is being incentivised, and there are currently commitments to implement this initiative by the 16 leading extractive companies in Colombia, which represent 80% of mining production.

- In the health sector, ACTUE-Colombia has been supporting what some call “radical transparency†in the country’s pharmaceutical policy, with a view not only to guaranteeing right of use and access to a quality and transparent service but also to recovering citizens’ trust in the sector. To assure these objectives, initiatives have been developed that involve various stakeholders and donors, such as the Decalogue for Transparency and Integrity in the health sector, and tools for access to information have been implemented, such as the Medicamentos a un Clic [One-click Medicines], a web platform for health professionals, and the Termómetro de Precios de Medicamentos [Medicine Price Thermometer], among others.

- Additionally, ACTUE-Colombia supports the commitment of the national government to promoting a cultural change, as there is wide recognition that the laws are important but insufficient. Along these lines, the Pedagogic Routes for Promotion of Transparency, Integrity and Safeguarding the Public Good have been implemented with the aim of raising awareness in school and university classrooms and in public institutions of their role in this cultural change in personal and institutional conduct.

Citizen participation and the private sector: Both citizens and businesses are key players in the fight against corruption. To create a healthy, upstanding and aware society, it is necessary for them to be participants in the cultural, institutional and regulatory changes.

- To promote the shared responsibility of business owners in the prevention of corruption, continuity has been given to initiatives that promote business ethics, self-regulation, bribery prevention and clear rules, such as the Registry of Private Companies Active in Compliance with Anti-corruption Measures (EACA) and the Handbook of Transparency and Anti-corruption Business Agreements.s

- To engage civil society in the fight against corruption and the promotion of transparency and integrity, support has been given to actions such as strengthening of the National Citizen Council for Fighting Corruption, promotion of a “Friends of Transparency” network and improvement of accountability in citizen participation forums, as well as in NGOs, among others.

Territorial Open Government: The change must take place at all political levels, from the national government to territorial governments. This area strengthens regional and local capacities in the implementation of the law on transparency; attention to citizens and management of corruptions risks; promoting citizen participation, social control and accountability. Additionally, the creation of a network of open governorates is being driven with a view to promoting exchange and peer-to-peer learning.

The coordination work and the comprehensive approach of ACTUE is facilitating the steps being taken towards real change in Colombia, however ending the culture of corruption is a task that requires the commitment and joint work of all stakeholders in Colombian society.